Hey my friend, welcome back! Today we’re going have a special talk.

Hello V, what’s that? Is this another coffee break?

Hm… not exactly.

It’s about a new ambigram type. Not just a new type, a whole new category!

Wait, what? Really? Does the title “filter” have to do something with it?

Yes. I’m not sure of the best way to introduce it. I think I’ll just share it and get the conversation rolling. Are you ready?

Of course!

Great! Here’s a piece from Otto Kronstedt. It’s called “Hide in plain sight”.

Can you see what happens here?

I read ‘plain sight’ when it’s in focus and then I read ‘hide’ when it gets blurry.

That’s right. But let me ask you something. Do you think that this piece belongs to the mind category or the geometric category?

Hm… I would probably say ‘mind category’. But also, a transformation there, so does it belong to the geometric category as well? Can that be the case?

You’re right that there is a transformation there. We have the first image, then it gets blurry and we get the final image. As for the category, let’s remember the core function of an ambigram first, and test both options.

The core function of an ambigram is this:

• I read something

• Something happens

• I can read it again

If “something happens” to the art, we have a geometric ambigram.

If “something happens” to the viewer’s mind, we have a mind ambigram.

Let’s start by assuming that Otto’s piece belongs to the mind category. What would that mean? It would mean that “something happens” to our mind, the viewer’s mind. But that’s not the case here. We obviously see a transformation. This image gets blurry. Mind ambigrams are still images. Motionless art, with no transformations. Mind ambigrams require the viewer to change their perception and read something else by just looking at a still piece of typography. Otto’s piece displays an animation from the focused image to the blurry one. It’s not motionless. What happens here is not just in the viewer’s mind, it happens to the art. So, it cannot be the case that ‘hide in plain sight’ is a mind ambigram.

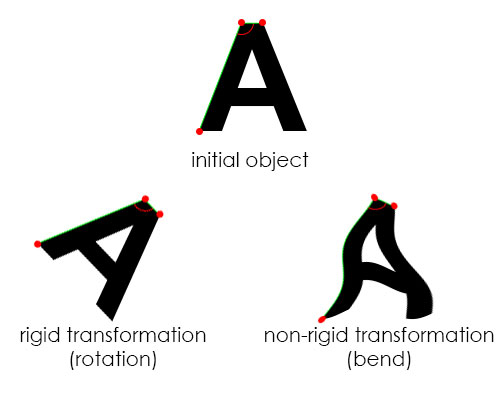

It must be a geometric ambigram, right? Well, let’s test this assumption as well. Do you remember what categories of geometric transformation there are? We talked about it here. There are rigid transformations and non-rigid ones. There are three rigid transformations: rotation, reflection, translation, and they preserve the original shape, size, angles, dimensions of an object. On the other hand, non-rigid transformations alter those qualities. Such transformations are: bend, twist, shear etc. Here’s an example for the visual learners.

In every geometric transformation, you can always map the vertices (red) and edges (green) of an initial object to the transformed version of it. Also, you can clearly say if a specific point is inside the shape (it will be black) or outside (white).

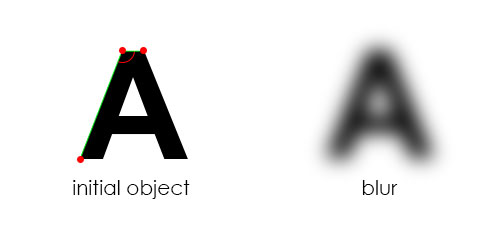

But let’s see what a blur is.

In the blurred image, you cannot map exactly vertices from the initial object. Nor can you exactly map the edges. And you cannot say for sure if a specific point is inside or outside the shape. It’s not just black and white, it’s gray! If you point at somewhere, it will probably be gray, let’s say 30%. What’s that? Did we point at an edge? Did we point inside or outside the inital object? We’re not sure. If that was indeed a geometric transformation, we would be able to answer all of that.

So clearly, blur is not a geometric transformation either. Which means that “what happens” in Otto’s piece does not happen to the art itself. That’s leads us to think…

If the transformation does not happen to the art itself, nor to the viewer’s mind, where does it happen?

And the answer is simple…

In between!

In between?

That’s right my friend, in between. The artist created his piece and in order to achieve duality, he cleverly placed something in between you, the viewer and the art. He added a…